Engine Failure in the Arctic

(But Not Late For Turkey)

And so it began...

It was the end of another season of float flying in Inuvik. Freeze-up was upon us, and the lease agreement between myself and the local float operator for my Cessna 180 was at an end. My wife, Andrea, had left for Edmonton the week before, and it was time for me to fly south to the more temperate, always float-flyable climes of BC's west coast. It was not planned to be a direct route though; I was going to fly to Cooking Lake, Edmonton, to pick up Andrea and then set out for Iskwatikan Lake, SK. Iskwatikan Lake, about 30 nm north east of La Ronge, is home to a small fly-in fishing lodge operated by some friends from Inuvik. It just happened that we were invited for Thanksgiving turkey dinner on October 7th, and although not exactly 'on the way' to BC from Inuvik, we weren't about to refuse!

The days leading up to my departure had been spent packing up what was left of my belongings and helping the company mechanic replace a jug on the 180. Not that it needed replacing, but the previous week the company's 206 burned a valve and in a desperate move the company took one of my 180's cylinders to get the 206 up and running. Not to worry, I was promised, a new cylinder would be installed on my airplane in time for me to be on my way. After much urging and prodding, and about two days later than planned (I was originally trying to leave on October 1st or 2nd) , the cylinder was installed and signed off.

October 4, 2001

Everything loaded and preflighted, I fired up at 12:45pm and taxied out to the end of Shell Lake and not a moment to soon; I had to break ice on Shell Lake that morning to get out. Another day would mean permanent residence in Inuvik for the 180. With CHTs in the green, I did a run-up and blasted off for Norman Wells, my first fuel stop. Under normal circumstances I would have the range to reach Fort Simpson, but with the new cylinder to break in I would be running the engine harder than normal and burning extra fuel.

Other than headwinds, it was an uneventful trip to the Wells. I tied up at the float base and called North-Wright Air for fuel. After the requisite bathroom pit-stop and call to FSS, I was on my way again. The weather in the Wells and to the south was wide open VFR and winds swung to the northwest giving me an always welcome push southward. My routing out of the wells was direct to Fort Simpson which took me pretty much up the McKenzie River.

|

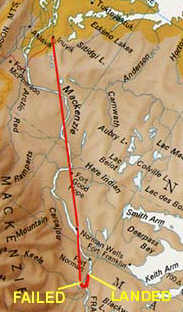

| I departed Inuvik, NT, and flew direct to Norman Wells. After fueling I continued direct to Fort Simpson. The track put me about 3 - 5 miles west of the Mackenzie River at the time of the failure, 71nm southeast of the Wells. I followed the Keele River eastward to the Mackenzie and then turned northward. A Canadian Helicopters Astar 350 was working in Fort Norman (Tulita) at the time and came by to pick me up. |

The

bad news came at 16:55 local time, 71nm south east of Norman Wells while

cruising at 3500 feet: I gave the prop control a twist to adjust the RPM and was

rewarded with a couple of sharp bangs (actually, they sound more like 'pops'

through the headset) and uncontrollable, violent shaking. Instantaneously, two

things went through my mind: 1) This was going to be very expensive for me; and

2) It must be that new cylinder that was just installed. I retarded power to

idle to decrease the severity of the shaking and ran through the usual checks

but to no avail. Certainly something serious had failed in the engine and I had

no way of correcting it from my seat in the cockpit. I trimmed for best glide,

radioed Norman Wells FSS to inform them of my situation, and began deciding on a

landing place. For those not familiar with the arctic, it is not a matter of IF

you can land somewhere on floats, but WHERE you should land. There are hundreds

of rivers and lakes dotting the tundra. My biggest concern was that freeze-up

was starting and I didn't want to set down in a lake and end up with the

aircraft trapped in the ice. It was clear I'd have to find a good spot on a

river (because of the moving water, rivers stay open much longer than lakes) to

put down. I quickly decided that my best choice would be the Mackenzie River.

If I was lucky, I could have the plane loaded onto the last river barge of the

season and shipped back to Norman Wells. So there I was, decending out of 3500',

the Mackenzie River a good 5 miles east of me and the Keele River just sliding

under my nose. I turned east and followed the Keele to the confluence with the

Mackenzie where I turned back north towards Norman Wells. Might as well close

the distance between me and civilization -- at the very least it will keep the

recovery costs down. As I descended below 2500 feet I lost contact with Norman

Wells FSS. A helicopter working a survey in Tulita, about 20 miles from my

current position began to relay back to FSS for me. I knew that beaching the

plane on the Mackenzie would be risky; with no trees to tie to and a swift

current, it would be difficult to secure the aircraft until I could get it moved

to safety. Knowing this I scanned for any form of shelter. I was quickly

rewarded with a long estuary which extended inland about 100 meters and was

protected from the river current. I glided overhead, down to about 900 feet now

and radioed the proposed landing co-ordinates to the survey chopper who passed

them onto FSS. That done, I had only a landing left to accomplish, which went

off very smoothly. And why shouldn't it? It's no different that what I do a

dozen times a day. I heeled the aircraft up onto the shoreline as far as I

could. I took a couple 100' ropes and secured them from the aircraft to the

biggest logs I could find, then piled rocks and boulders in front of the logs to

create additional anchorage. I wasn't concerned with the current sweeping the

plane away (there was none in this estuary), but moreso with any wind that may

come up and drift the aircraft from shore. Shortly after getting down safely,

the survey helicopter came by and landed on beach. Ralph, the pilot, was kind

enough to give me a lift back to Norman Wells. What a relief! I didn't relish

the idea of spending any time on that desolate shore.

The

bad news came at 16:55 local time, 71nm south east of Norman Wells while

cruising at 3500 feet: I gave the prop control a twist to adjust the RPM and was

rewarded with a couple of sharp bangs (actually, they sound more like 'pops'

through the headset) and uncontrollable, violent shaking. Instantaneously, two

things went through my mind: 1) This was going to be very expensive for me; and

2) It must be that new cylinder that was just installed. I retarded power to

idle to decrease the severity of the shaking and ran through the usual checks

but to no avail. Certainly something serious had failed in the engine and I had

no way of correcting it from my seat in the cockpit. I trimmed for best glide,

radioed Norman Wells FSS to inform them of my situation, and began deciding on a

landing place. For those not familiar with the arctic, it is not a matter of IF

you can land somewhere on floats, but WHERE you should land. There are hundreds

of rivers and lakes dotting the tundra. My biggest concern was that freeze-up

was starting and I didn't want to set down in a lake and end up with the

aircraft trapped in the ice. It was clear I'd have to find a good spot on a

river (because of the moving water, rivers stay open much longer than lakes) to

put down. I quickly decided that my best choice would be the Mackenzie River.

If I was lucky, I could have the plane loaded onto the last river barge of the

season and shipped back to Norman Wells. So there I was, decending out of 3500',

the Mackenzie River a good 5 miles east of me and the Keele River just sliding

under my nose. I turned east and followed the Keele to the confluence with the

Mackenzie where I turned back north towards Norman Wells. Might as well close

the distance between me and civilization -- at the very least it will keep the

recovery costs down. As I descended below 2500 feet I lost contact with Norman

Wells FSS. A helicopter working a survey in Tulita, about 20 miles from my

current position began to relay back to FSS for me. I knew that beaching the

plane on the Mackenzie would be risky; with no trees to tie to and a swift

current, it would be difficult to secure the aircraft until I could get it moved

to safety. Knowing this I scanned for any form of shelter. I was quickly

rewarded with a long estuary which extended inland about 100 meters and was

protected from the river current. I glided overhead, down to about 900 feet now

and radioed the proposed landing co-ordinates to the survey chopper who passed

them onto FSS. That done, I had only a landing left to accomplish, which went

off very smoothly. And why shouldn't it? It's no different that what I do a

dozen times a day. I heeled the aircraft up onto the shoreline as far as I

could. I took a couple 100' ropes and secured them from the aircraft to the

biggest logs I could find, then piled rocks and boulders in front of the logs to

create additional anchorage. I wasn't concerned with the current sweeping the

plane away (there was none in this estuary), but moreso with any wind that may

come up and drift the aircraft from shore. Shortly after getting down safely,

the survey helicopter came by and landed on beach. Ralph, the pilot, was kind

enough to give me a lift back to Norman Wells. What a relief! I didn't relish

the idea of spending any time on that desolate shore.

It sure didn't look like I was going to make it for turkey that Thanksgiving.

Back in Norman Wells I contacted North-Wright Air and filled them in on my little drama. Warren Wright, owner of North-Wright, offered me one of his AMEs for a few days work to get me on the road again. Also, I made arrangements to charter the only floatplane left in town, their Pilatus PC-6 Porter. Not that I have anything against the Porter - it's an amazing airplane - but I didn't relish the thought of paying for the Porter to fly only myself and one engineer up the river. Unfortunately, it turned out to be the only viable choice. The last river barge of the season had come and gone, and a boat charter was nearly the cost of the Porter. And you can be sure that the thought of maybe, just maybe, making that turkey dinner helped my subconscious decide to fork over the extra dollars for the convenience of the speed of traveling by air. It was getting dark now so it was decided to leave at 0800 the next morning. Warren was gracious enough to allow me to stay at his pilot's accommodations which was very much appreciated.

October 5, 2001

Dru Taylor, the North-Wright AME came by to pick me up bright and early. We headed down to the float base where we met the Porter pilot. It was definitely my lucky day because he had originally planned to fly out for BC, but was talked into doing this one last trip. We blasted off and 25 minutes later touched down and taxied up to my stranded 180. We had everything decowled in a matter of minutes and began the diagnostic work. The first, and obvious item to check was the new cylinder that had been installed. We removed the rocker box cover and wouldn't ya know it? A few loose pieces were discovered: 1 exhaust rocker arm, 1 exhaust rocker arm shaft, 1 broken piece of cylinder head boss, and 1 bent exhaust pushrod. Strangely absent were the bolts that hold the rocker arm shafts in place. They had been forgotten when the cylinder was installed only two days before! What had happened was now clear. Without those rocker shaft bolts, it was only a matter of time until one of both of the rocker shafts worked loose from the cylinder head. In my case, the exhaust side won the race. When the shaft finally came free, and the pushrod came up on the next cycle of the engine, it snapped the shaft out of the remaining boss and permanently closed the exhaust valve. With the piece broken out of the cylinder head it was clear that a new cylinder was required. The idea of installing one here, over the water, was not appealing (every float pilot knows you need at least 2 of everything when you work over water). It was decided to patch the existing cylinder up enough so that I could limp back to Norman Wells were a proper repair could be carried out.

We re-assembled the broken cylinder head boss with the rocker arm and shaft installed and held it together with safety wire. We tapped the head to fit a bolt in place to help hold everything together, and carved a small piece of driftwood (yes, I actually carved engine parts from driftwood) to act as a third and final guard against the rocker shaft from slide out again. The bent pushrod was knocked straight with a hammer as best we could. It all seemed pretty 'duct-tape-Red-Green Show-ish', but it only had to last 25 minutes to get me back to Norman Wells.

|

|

|

| This picture was taken after the cylinder was removed from the aircraft. You can see the broken rocker arm shaft boss near the middle of the image. When it let go, the exhaust valve ceased to function, back-feeding exhaust gasses through the intake and "choking" the engine. | To fix the problem we re-assembled the broken boss, rocker arm, and shaft. Safety wire and a spare, albeit poorly fitting, bolt held everything together. We also installed a bolt into the boss for the intake valve, as it too was missing. | To ensure that during the 25 minute flight back to Norman Wells the shafts didn't work themselves loose again (eg: if the safety wire broke or if the bolts came loose - they were not the correct bolts for the job and the fit was poor) we whittle a piece of driftwood to fit nicely between the shaft bosses. |

With the plane cowled up again, it was the moment of truth. The plane fired right up: so far so good! I taxied out of the estuary and into the main channel of the river. If it was going to fail, it would be during takeoff which required the highest RPMs and thus the most rigorous test of our modification. I set the prop control to where I approximated 2500 RPM to be (instead of the usual 2800) prior to applying full power. The lower RPM would mean longevity to our 'driftwood mod.' Fortunately, everything held for the trip back to Norman Wells. The takeoff was fine, and the trip down river was completely uneventful. I'm sure I breathed a big sigh of relief when I touched down back in the Wells. No matter what happened now, at least the plane was in civilization.

We hauled the plane out of the water and began repairs immediately with all

parts, including the replacement cylinder, supplied by North-Wright Air.

Unfortunately, because it took so long to recover the plane, it was already

getting dark and all that could be accomplished was the removal of the failed

cylinder. While removing it, several other minor problems were discovered that

would also have to be rectified before I would risk further flight across the

barren arctic. At that point I decided that it would be prudent to have Dru

check over the entire engine and airframe, akin to a mini-100 hour inspection,

to ensure that there were no other 'mistakes' lingering from previous

maintenance. Certainly, another day would have to be spent in Norman Wells.

October 6, 2001 - The Day Before Thanksgiving

|

All Done! Drury & family join me for a good luck photo before we put SLA back in the water. |

Again, early in the morning Dru came by the North-Wright staff house to pick me up. We proceeded straight down to the plane to continue our repairs. Somehow, I had imagined that we'd be completed by the late afternoon and I'd be able to make it to Fort Simpson by night. Of course, the mind's eye is never very good at estimating time and mine is no exception. By 4pm that afternoon with dusk fast approaching, we had the new cylinder mostly installed, the engine completely checked over (and a few minor problems corrected) and everything just about ready to go. We worked efficiently, but the detail work caught up with us. By the time the aircraft was completely cowled up, test run, put back in the water, and fueled up, it was after 10pm.

October 7, 2001 - Thanksgiving

I called FSS first thing in the morning and was pleased to find that the weather, while not clear, was VFR the entire way to my destination. Because of my engine failure induced delay, the Thanksgiving dinner plans were changed. If I had any chance of getting to Iskwatikan Lake in time for dinner, I would have to fly as directly as possible, bypassing Edmonton and hence not picking up my wife. Of course, after the engine failure, Andrea and I both realized that it was unlikely I would be picking her up in Edmonton so she had already made her own arrangements to get to Iskwatikan Lake. I filed my new route with FSS which was to be direct Norman Wells to Yellowknife, where I would fuel up, continue on to Uranium City, SK, for another fuel stop, and then finally to Iskwatikan Lake, SK, in time for dinner.

Dru picked me up bright and early and took me down to the float base where my once-again-whole Cessna 180 was waiting patiently, fully fueled and ready to go from the night before. The PC-6 had left the day before, and I was the last float plane on the lake this year. I wave good-bye, taxiied out, opened my flight plan with FSS and blasted off. I followed the Mackenzie for a while to make sure that everything was working properly before turning eastward for Yellowknife.

A total of 8.3 flight hours later, after fuel stops in Yellowknife and Stony Rapids (I originally stopped at Uranium City but was unable to find anyone to fuel me), as the sun was sinking below the horizon, I finally arrived at Iskwatikan Lake. My relief at having finally completed my journey was tremendous. Only three days before it seemed as though I would never make it, and now here I was, even 15 minutes early for dinner.

And how was the dinner? Fantastic.